London has had a tough time of it in recent years, in literature and to a lesser extent in life: it’s rioted and rebelled; it’s been burned, bombed and buried; it’s risen to great heights and, inevitably, it’s fallen. And fallen. And fallen.

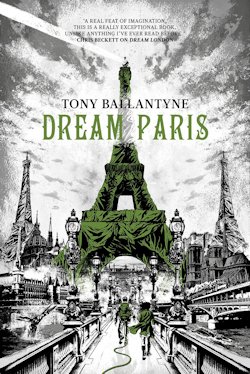

But you can’t keep a city like Great Britain’s biggest down—even when a living nightmare threatens to take its place, as Tony Ballantyne demonstrated in Dream London. A notable novel which explored a notion not dissimilar to that proposed by the Philip K. Dick Award nominee’s pre-eminent peer in the weird, namely the intrusion of a second place on a single space—see also The City & the City by China Mieville—Dream London showcased the spirit and the resilience of even the most impoverished inhabitants of my country’s capital.

If you weren’t here, if you didn’t live through the changes, if you didn’t experience how the streets moved around at night or how people’s personalities were subtly altered, if you didn’t see the casual cruelty, the cheapening of human life, the way that easy stereotypes took hold of people… if you weren’t there, you’re never going to understand what it was like.

Anna Sinfield remembers, however. Anna Sinfield will never forget.

And yet, having lost her mother and her father and her friends to the dream world’s dark designs, she still found a reserve of strength inside herself. Alongside thousands of other like-minded Londoners, she marched into the parks when all was almost lost, the better to bring down the Angel Tower and stand against the source of the so-called incursion.

Dream London has been receding steadily ever since. The streets are straightening; people’s personalities are reasserting themselves; human life means something once more. But for Anna, a secondary character in Ballantyne’s last, I’m afraid the nightmare is far from over. When a man with fly eyes called Mr Twelvetrees presents her with a prophesy that promises she’ll be reunited with her missing mum in Dream Paris, she packs a bag without missing a beat and sets her sights on the City of Lights.

She expects to make landfall in a landscape much like Dream London—as did I; I’d imagined another living city, distorted just so from the one we know—but the dream world’s France is in fact fairly familiar:

In Dream London everything was shifting and growing. There, it was like the city was moulding people and places into what it wanted to be. Here, it’s like the people are stronger. They fought back against the changes, they moulded things to suit themselves.

To wit, Dream Paris revolves around revolution; around revolting, repeatedly—every twenty years, it appears—against the Powers That Be.

When Anna and Francis, the chaperone Mr Twelvetrees insists she take with her, finally arrive in said city, the Powers That Be are delegates of the Banca di Primavera: a financial facility everyone owes something to—not least the clay creatures that walk the streets like real people—and can be counted on to call in its debts when you least expect.

But to begin with, the Banca is good to Anna and Francis: it gives the pair a place to stay; it offers them invaluable advice, including the first clues about where Anna’s mother might be; and it insists it’s doing all this simply for the sake of liberté, égalité, fraternité. It’s to her credit that Anna quickly questions its interests, but by then she’s already up to her seventeen-year-old ears in arrears; a debt the agents of the Banca di Primavera—china dolls et al—are determined to collect.

Given the very real threat they represent—a threat best embodied by a particularly grim lynching at the back end of the book—you’d be forgiven for thinking Dream Paris a thriller, but if it is, it’s only eventually effective. Though there are several shocking scenes and beaucoup betrayals, they take place too late in the tale to have the intended effect. The end result of this is—at least in advance of its practically apocalyptic last act—a markedly more whimsical walkabout than that documented in Dream Paris‘ disconcerting predecessor, which lashed its more outlandish moments to the inscrutable interests of an urban entity that recognised no known rule: not humanity, not gravity.

Absent that kind of connectedness, Dream Paris‘ weird centrepieces can feel unfortunately fleeting. Take the eating competition Anna accidentally enlists in; a so-called “Dinner of Death” that culminates in a conversation with a carnivorous calf. Whilst perfectly diverting and deftly depicted indeed, the meal, in the moment, is almost completely meaningless: it adds nothing to the narrative, it doesn’t develop Anna’s undercooked character, and its setting, in the scheme of things, is insignificant.

The proliferation of such incidental silliness in Dream Paris is a problem, as is the sense that Anna is “allowing things to happen to her, rather than controlling events.” That said, the journey is altogether enjoyable, and the destination deliciously twisted.

To boot, Ballantyne’s social satire is as sharp here as it was in his last, particularly his portrayal of language as a medium of oppression as opposed to expression. By enumerating pronouns such as tu(2) and (2)vous, like so, “the aristocracy of Dream France could invest an exact measure of authority into every conversation,” leading to a lot of literal power-plays grammar fans are apt to appreciate above and beyond the content of the actual conversations.

This, then, is a story about “the difference between the appearance and what lies underneath,” and in that sense, it’s a success, but to my grumpy old man mind, Dream Paris‘ more playful—nay, inane—nature means said sequel isn’t a patch on its absurdly powerful predecessor.

Dream Paris is available August 25th in the US and September 10th in the UK from Solaris.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.